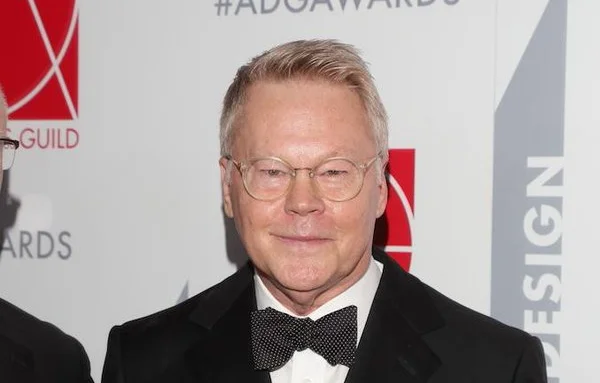

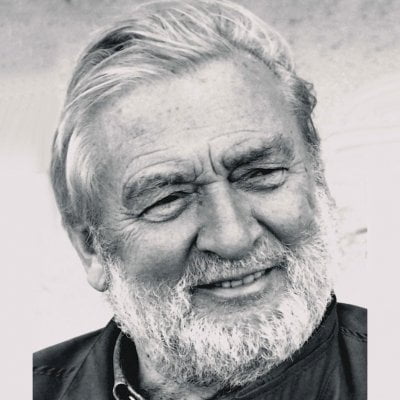

Jean Prouvé

Jean Prouvé

designer

- Birth: April 8, 1901

- Died: March 23, 1984

- Nationality: French

Jean Prouvé was a French metal worker, designer, and architect of the early modernist movement. Prouvé is widely appreciated for introducing industrial manufacturing techniques, and an industrial aesthetic to interior design. He initially trained to be a blacksmith, then attended engineering school in his native Nancy. In 1923 he opened a workshop, where he produced wrought iron lamps, chandeliers, and other household objects.

He soon expanded his range to include metal furniture of his own design. Throughout his career, Prouvé displayed more interest in the materials and the production process than in form alone and considered himself more of an engineer than a designer. His goal was to create unpretentious, materially efficient products. He wrote architectural history again in 1971 when he led the jury for the competition for the construction of the Center George Pompidou and made a decisive contribution to the implementation of the piano and Rogers design. From letter openers to door and window fittings, lights, furniture, facade elements, prefabricated houses, modular building systems to large trade fair and exhibition buildings, Prouvé’s work encompasses almost everything that requires an industrial production method.

by Jean Prouve for Vitra

In 2002, Vitra, in close cooperation with the Prouvé family, began to reissue designs by the great designer.

When Jean Prouvé desired to focus, he enjoyed leaning the seat. “My dad loved balancing on the trunk of the chair,” says his daughter Catherine. “He had been the only one from the family who was able to sit on two legs” It was probably also due to the seat that the designer managed to maintain his balance so virtuously. His famous”Standard Chair” includes a vast region of the weight reduction on the rear legs. This silent classic made from plywood and brushed sheet steel, made in 1934 and further developed in 1950, is currently beating kitchens and dining rooms all around the world again since its strong charm fits so nicely with this”industrial chic” of urban lofts.

The design of Jean Prouvé

However, Prouvé didn’t think much of chic. Functionality and lightness were the top priorities for his designs. “Furniture must fix issues as complicated as large building constructions,” explained Prouvé,” which led me to style them with identical care, according to the very same statics legislation, and even in the very same materials.” Like most of his contemporaries, he detected steel for a material. However, the steel tubing, as favored by Marcel Breuer, Mart Stam, and Le Corbusier, wasn’t strong enough for him.

He cried the high-gloss nickel and chrome appearance of his period together with rough-painted steel, thus producing the industrial nature of this substance visible. And where the contours of the normal 1950s design taper softly, Prouvé used conical elements, likely legs which produce his furniture seem more lively than tasteful. The structure was more important to him than the true form. His furniture wasn’t made on paper, but at the workshop, in cooperation with engineers and engineers. A first layout drawing was used as a prototype, then exposed to a stability evaluation and adjusted. After a version was accepted, the furniture has been created in small series. Thus Jean Prouvé was independent of outside firms and managed to produce in tiny amounts. The business grew. Prouvé not just developed furniture, but also facade components for architects.

After World War II broke out, metal became rare and costly. While manufacturing nearly came to a standstill, Prouvé became involved with the immunity and took good care of the food source for its own employees. In 1945 he had been Mayor of Nancy to get a couple of months. Following the war, he also developed crisis shelters and cellular school buildings out of factory-made metallic panels which were constructed on site.

For a dad, Jean Prouvé was a patriarch – he comprised cousins, brothers and his kids in the corporation. In Prouvés in the home, everything revolved around the corporation. “We lived in a home filled with prototypes,” remembers Catherine Prouvé, “along with also my mom hosted the architects, staff, and students which my dad brought to dinner” As a company, Prouvé understood how to inspire its workers through bonuses, additional training and paid holiday.

The technology-loving designer adored automobiles, notably convertibles, and possessed various versions from Citroen, Talbot, Triumph and Alfa Romeo, but aside from thathe wasn’t used to piling possessions. What his firm produced in gain has been invested in new machines, the remainder was spread as a bonus to the workers. The entire company was democratic and lively as the”Standard Chair”. The famous”Esprit Prouvé” stayed after the firm grew to over 200 workers and proceeded to Maxéville from the Nancy industrial region in 1946.

The Close of the Organization Prouvé made raising investments in Maxéville to be able to have the ability to manufacture factory-made homes with which he wished to fulfill the excellent demand for homes following the war. Some reveal homes were constructed in Congo’s Brazzaville, but they had been too pricey for the African American market.

In Maxéville, profits were becoming smaller. To be able to continue investing, Prouvé awakened with Studal, a company in the aluminum market. There were monetary injections, but it required more and more company shares. When there were no significant orders for the metal homes, the management board called for the restructuring of the provider. Prouvé was due to its decision-making power in 1953 and was no longer allowed to join the production halls. It was a tragedy for the “homme d’usine”. Even worse was that with the studios he lost the right to his or her patents. Prouvé was no more allowed to construct Prouvé. It was the year in which Studal gained a vast majority stake.

The life after

“Your wings have been trimmed. Help yourself with what’s left to you,” his buddy Le Corbusier advised him later dropping Maxéville – and Prouvé did. Back in 1954, he built a house for his family of six in Nancy with remnants from Maxéville, which was his manifesto of modern living: small bedrooms, but a massive living space in which the family came together. Furniture manufacturing came to a standstill when Maxéville failed. Prouvé developed furniture theories together with Charlotte Perriand, but there were no new furniture designs.